Barrie Wentzell worked as chief photographer for the UK's Melody Maker, "a professional musician's paper," from 1965-1975. His photographic credits are extensive and include amongst them, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix and many more.

His first job was working at a design company in Soho. He got his introduction into the flamboyant world of the performing arts at age 16. When the design company closed its doors, Wentzell landed his next job with a photographer in London's Belgravia section. He mixed chemicals in the flat's basement darkroom, learned about lighting and borrowed his boss's Leica camera. He shot in pubs, restaurants, cafes and on the streets.

Wentzell honed his darkroom skills at the London School of Printing and then met Maurice Newcombe, a freelance photographer who took theatre pictures for the Daily Telegraph.

He went to the BBC and it was there that he met Diana Ross. He asked to photograph the up and coming singer and she agreed. He then "dropped a few snaps into the Melody Maker" and that's when things markedly started to change for him.

Bob Houston, the assistant editor at Melody Maker, called him a week later and offered him a steady job as chief photographer.

After 10 years with the paper he left London and Melody Maker in 1975 and relocated to the Isle of Wight.

I met with Barrie Wentzell at his eclectic Toronto studio on November 20, 2005. We sat at his round table, shared wine and cigarettes and talked about a revolutionary decade in the history of rock.

What was it like being a music photographer in London in the 60's and 70's?

It was an exploratory time. That whole thing out of the 60's started something despite England being very conservative, like the rock and roll thing, everybody joined in with that. The city gents were hip, the Queen was hip, the guys wearing the busbies were cool. It was like everything English was fabulous. England was like a tiered class system; but with music, rock and roll and art, you could speak to lords, earls, kings as well as the tramps on the street.

How did you end up becoming a rock and roll photographer?

I heard some 78's of Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley and Fats Domino and I thought, wow that's amazing, I wanna be involved in that.

So what did you do?

I became a recluse [laughter]. I didn't wanna do anything and then me mum [Ann] said, "Well you've gotta have a job." So she looked through the phone book and called places and I got an interview for a job in Soho on Greek Street.

It was a supposed advertising, design company. I showed up for work and a guy with blue hair, make-up, a kimono shirt, leotards and bare feet stood at the door and said, "Ah, you must be staff. I'm Mr. [Quentin] Crisp."

The Naked Civil Servant. What was he like?

He was an amazing, courageous chap. He was way ahead of his time, a dead [real] individual. Years later when I was doing the rock and roll thing, taking pictures of Bolan and Bowie I thought, I've already been here and now it's kosher [laughter]. I met a lot of people from other planets! The most amazing characters showed up there; prostitutes, strippers, gangsters, artists, transvestites.

Tell me about meeting Maurice Newcombe.

He said to me, 'Here, d'you wanna job, I need someone to print my pictures?' So I said, I can do that. The wage was measly, but the "benefits" outweighed the pay. Maurice was connected and he gave me his "invites" to the BBC and West End theatres and suggested I shoot some of my own stuff.

What was working for Melody Maker like?

I was walking down Charing Cross road one day and there was my picture [of Diana Ross] on the front page with a photo credit. Melody Maker was the bible, everybody read it. It took things seriously. I went  along to the meetings. I was offered more money and the editor started using the pictures really big, a whole front page and articles. It was a fantastic period. The Beatles didn't know they could do Abbey Road and we didn't know we could shoot the covers of Melody Maker.

along to the meetings. I was offered more money and the editor started using the pictures really big, a whole front page and articles. It was a fantastic period. The Beatles didn't know they could do Abbey Road and we didn't know we could shoot the covers of Melody Maker.

Which was the first band you recall seeing live?

The first band I remember seeing were The Rolling Stones, and then there were The Kinks, The Yardbirds, and The Pretty Things. We went out and started discovering bands, writing and photographing. Our editor didn't know what was hot or not and we had an amazing amount of freedom. We practically ran the paper ourselves.

What was your approach as a photographer?

Frame, shape and leave space. I'd learn how to take the picture the way it would appear in the paper. I'd shoot sequentially. In the beginning people invited you, it was very open, there were no barriers, there were no management hassles, no  make-up artists, stylists, people were just as they were. I was learning how to make pictures while others were learning how to play the guitar. Everybody was learning. It was about making it up as you went along, the technology we have today, came from that.

make-up artists, stylists, people were just as they were. I was learning how to make pictures while others were learning how to play the guitar. Everybody was learning. It was about making it up as you went along, the technology we have today, came from that.

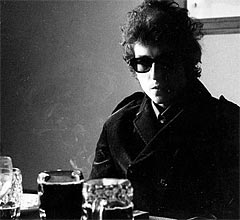

When you found yourself in a room with Bob Dylan, for instance, what would you do?

Be invisible. You get them engaged. You focus on the eyes. You have that connection as artist to artist, rather than photographer to star who doesn't wanna know about it. There was an intimacy and a trust and if you can get that, then it can work. You gotta break the ice somehow or allow it to melt, so there isn't a barrier between you. I think with my pictures I didn't want a barrier between what I see [gestures in front of himself] and what that actually is. It's gotta be truthful. It's a mirror somehow, between who I am and what I see, how they are. This is what it is, getting an intimate atmosphere, like it isn't a big deal.

What was going on in your mind when you were photographing?

It wasn't an intellectual thing; it was an intuitive thing. You wait for the moment, like Henri Cartier-Bresson said.

Who were your influences?

There was nobody to follow doing music photography. There was William Claxton who did the Chet Baker stuff and I liked Eugene Smith and Cartier-Bresson.

You shot so many brilliant singers and musicians. Who were some of the ones that stood out for you and what were they like?

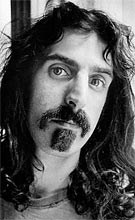

Frank Zappa was a ringmaster. He was a composer. He was forthright and serious. Keith Richards; he was in it for the music, like Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton, just raw blues. John Lennon's Imagine should be reality. "Just gimmie some truth!" Ray Davies and Pete Townshend, also. I was part of something turning.

Why did you leave the city and the paper in 1975?

It didn't feel real anymore. We were living and working the rock and roll lifestyle for ten years straight. I don't know how we did it, produced so much as well as had so much fun, but everybody was equal. The music came first, but [then] the commercial took over. I just felt like I don't wanna be here anymore. It all became about selling units.

Do you have any interest in photographing any singers or musicians at this point?

I'd rather photograph beautiful women or clowns [laughter].

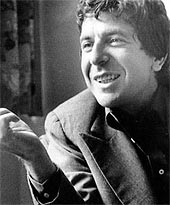

What music are you listening to currently?

Classical music, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen. I like Coldplay.

How do you feel about London?

It's got balls. It's got a great deal of audacity. It's got ego, but it's twice as fast and twice as expensive as the rest of the planet.

What do you think of the Canadian music scene?

Everybody knows Canadian talent and nobody knows it's Canadian. Canada can't boost its own talent. We make culture here and always ship it out to the rest of the world.

When you look back at what you accomplished, you must feel extremely proud.

The pictures come first. It's not about me, but there's a story related to the pictures.

You've "hit the bell" so to speak as a photographer. What would you say to an aspiring artist if they were to ask you for advice?

Tell your own story and never mind the bureaucrats! [laughter]

All images in this gallery are courtesy of barriewentzell.com.

Gallery by Mike McCaffrey

© 2006 Artzar.com - All rights reserved