How

have humans come to be the way they are? What has our journey been like?

Anthropology is concerned with these questions. Anthropologists use the

fossil record and inductive reasoning to try to understand the conditions

in which our species came to be in the state that we see it today. One

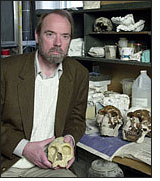

person with unique insight into the evolutionary process is Dr. Ian Tattersall,

55, Head of the Anthropology Department as well as curator of the Hall

of Human Biology and Evolution at the American Museum of Natural History

in New York City. Dr. Tattersall is the author of numerous books and articles

on human evolution as well as an authority on lemurs. Exhibits in the

Hall include a 3 million year old skeleton named "Lucy" along with an

evocative diorama whose construction was supervised by Dr. Tattersall,

examples of the first human implements and architecture, and a replica

of the 30,000 year old cave paintings of Lascaux, France. I interviewed

Ian Tattersall in his office at the museum on November 6, 2000.

How

have humans come to be the way they are? What has our journey been like?

Anthropology is concerned with these questions. Anthropologists use the

fossil record and inductive reasoning to try to understand the conditions

in which our species came to be in the state that we see it today. One

person with unique insight into the evolutionary process is Dr. Ian Tattersall,

55, Head of the Anthropology Department as well as curator of the Hall

of Human Biology and Evolution at the American Museum of Natural History

in New York City. Dr. Tattersall is the author of numerous books and articles

on human evolution as well as an authority on lemurs. Exhibits in the

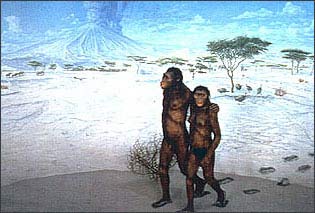

Hall include a 3 million year old skeleton named "Lucy" along with an

evocative diorama whose construction was supervised by Dr. Tattersall,

examples of the first human implements and architecture, and a replica

of the 30,000 year old cave paintings of Lascaux, France. I interviewed

Ian Tattersall in his office at the museum on November 6, 2000.

SHEDD: What does anthropology have to offer society?

TATTERSALL: Basically, the potential to answer a lot of curiosities. Human beings are very curious people. They want answers. In one area of human experience, anthropology has a unique perspective on those answers.

Are we still evolving?

No. We don't have the right conditions for any meaningful biological evolution of the species.

What kind of conditions would need to exist?

In order to get the fixation of evolutionary novelties and new things in populations, you need to have small isolated populations. Large, interbreeding populations are just not the right place for innovations to become fixed. As our species today is expanding, the population is becoming denser all the time; individual mobility is becoming greater, and so those conditions of the isolation of small fragmented populations just aren't there. You could imagine a scenario where they might be reestablished, but if things remain the same, essentially, no evolution.

How important is meat eating to our evolution?

It is very important to our diets. To our evolution, it is probably very important as well. Hunting came in at some point in human evolution and made a major revolution in lifestyles. We don't even know exactly when that was, but whenever it was, it certainly made a large difference.

Why is the human brain so large?

We have no idea exactly why humans have gotten the large brains they have today. It is clearly something in the human lineage that has predisposed humans to larger brain size, but we don't even know what the exact pattern was. All we can say is that 2 million years ago, average brain sizes among hominids were not much bigger than they are among apes today. 2 million years down the line, we have a brain that is 3 times that size. We don't know what happened in-between. We don't know enough about the number of species that have existed among hominids over the last 2 million years. We don't know enough about the time range of those species or the range in brain sizes. All we have is this simple observation that 2 million years ago our precursors had small brains and today we have large brains. We don't know what happened in the middle and we can't make the assumption that it was a linear transformation, linear gain in brain size. In fact, it almost certainly wasn't.

How important was fire in our cultural evolution?

That is a difficult question to answer. Because for start, there is some controversy whether the first claimed indications of fire, about 1.4 million years ago, are in fact instances of domesticated fire. Hearths, places that were specifically constructed to burn and domesticate fires in, don't come in until about 400 thousand years ago. At that point, there is clearly a major change in hominid lifestyles but, again, we don't know exactly what those major changes could have been. Clearly fire is a major factor in human life.

Why would speech be so important in Cro-Magnon development?

The Cro-Magnon are clearly symbolic entities. They are clearly forms that depended very much on symbolic reasoning to conduct their lives. We have absolutely no evidence among earlier hominids of symbolic reasoning. We know that the Cro-Magnon, who are a European group, essentially, are relatively recent. They invaded Europe about 40 thousand years ago and they came equipped with all these modern behavioral abilities. On the other hand, in the Levant, we have evidence of hominids who look just like us but behave just like Neanderthals as much as 100 thousand years ago. There is not a one-to-one correspondence with modern human anatomy and modern human behavior. You have to look for something, some potential that underlies symbolic cognitive processes but that had to be released in some way by some kind of cultural stimulation. Frankly, language is the most likely candidate. In fact, most people can't think of another one that might have released this potential and these new behaviors.

Were species co-existing before the Neanderthals and the Cro-Magnon?

Probably true. We tend to think, since we are the only hominid in the world today, that this is how it's always been. Clearly at one point we have evidence for 4 different species of hominids, around 2 million years ago on the same landscape in northern Kenya, let alone what was going on in the world as a whole.

What kind of people made the cave art in France and Spain?

The cave art is part of this whole Cro-Magnon behavioral explosion. The creators of that art were clearly modern people, not modern in a historical sense, but people with modern behavioral abilities. I can't think of a better example that you could put forward of the origin or the presence very early on of modern behavioral symbolic activities. What the art meant is a different question. It is to be experienced rather than explained.

What is the human capacity?

We are still discovering what the human capacity is. The human capacity is everything that makes us unique. And with every year that goes by we are exploring our capacities in new ways. We don't know yet what the human capacity is.

When did hominids first display the human capacity?

Basically the earliest evidence we have is from the Cro-Magnon in Europe, but there is inferential evidence from the very early occupation of Australia 60 thousand years ago by people who must have been quit extraordinary navigators to get there then. In Africa there are hints of symbolic behavior like making of beads and trading objects long distances and so on in the 40-60 thousand years ago range. There are these hints but the record isn't very good.

Why is burial of the dead so significant in human history?

It is something that only humans do in the world today and it is the earliest such behavior that we have found. Neanderthals probably invented burial of the dead but their motivations for doing so may have been very different from the kind of motivations that Homo sapiens have.

What are the impacts of the discovery of the Lucy skeleton?

It sort of inaugurated the modern era of studies of very early hominids in Africa. It was the only place where there are very early hominids. It was a catalyst that sparked a lot of later work. You could probably date the modern era of Paleoanthropology in Africa from that discovery.

Is she really named after the Beatles "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds"?

[laughs] I have no idea. Don Johanson would claim that's what it was.

Why bipedalism?

That is a very good question. There has been a lot of argument about why bipedalism and in fact that is maybe looking at it the wrong way. Did we stand up so we could shed heat better or so we could locomote better on the Savannah? Did we stand up so we could see further and detect predators better on the horizon? Did we stand up so we could free our forelimbs? All these things were probably involved. The fact is you have to stand up first and once you are able to stand up and walk erect then you have all the possibilities of this new posture available to you. And I don't really think it is possible to sort or separate them out individually. We bought a package. For whatever reason, those early hominids who stood upright ultimately were more successful, certainly in moving away from the forests. And that is what is important, the success of the species rather than any particular proclivity that this made possible.

Where did the concept for the diorama come from?

We wanted to choose one of the very few behavioral incidences for which we had evidence in the fossil record. It is very rare that you can isolate a behavioral moment. The reason why the diorama looks like it does is because it was the least committal statement that we could make about the circumstances under which it was made. You have got two individuals of different size, one with big feet, one with small feet, walking together and in step. So those two tracks must have been made at the same time by individuals walking together, and they are very close together indeed. You know that it could have been a large male and a juvenile or a whole number of different scenarios that might account for the size differences between the two individuals. We thought it would be visually most interesting to have a male and female, so that is what we did. They are so close together that they must have been braced together somehow. They must have been in some form of contact. Maybe they were carrying something but we have no idea what it might have been. They might have been holding hands. It seemed to us that any representation that we made would be loaded with implications, so maybe the implications of this particular scenario were the least.

Photo of Ian Tattersall by Denis Finnin.

Charles

R. Knight painting, "Lucy" reconstruction diorama,

courtesy American

Museum of Natural History Library.

Wallpaper graphic © Ian Tattersall.

Gallery Design by Mike McCaffrey