|

by Laura

Richard Janku

At

92, Louise Bourgeois is still producing vibrant, large-scale work

that continues themes explored throughout her career. "I

am a long distance runner and a lonely runner, and that's the way

I like it," she said in an interview conducted by

e-mail in June 2002. The ongoing success of Bourgeois' sculptures

lies in their ability to transcend the personal subjectivity of

the maker into collective, objective human experience. And in her

fresh and fearless approach to materials. But it is the personal

origin of the work that fuels its deep emotional impact.

|

|

|

|

Bourgeois translates

memory and feeling into a universal visceral visual language by

using materials in a way that heightens both their expressive value

and that of the form they describe. She commits herself to no particular

material or—like Gerhard Richter—style of self-expression,

preferring instead to mine all possibilities for the most potent

combination. Working in everything from fabric to bronze, she calls

forth the medium's shamanistic quality and uses it to construct

elemental forms that balance gracefully between rawness and restraint.

Despite the specificity of many titles, the work is more literary

than literal, invoking a pantheon of mythologic and psychologic

symbolism.

|

|

|

|

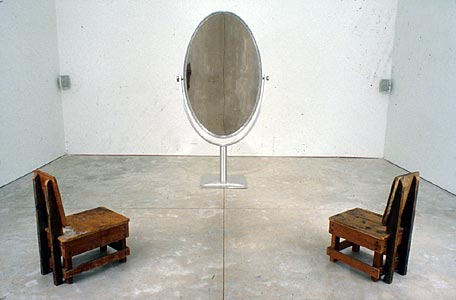

Her

recent solo show—the first in New York since 1994—at Cheim

& Read featured large narrative sculptural works comprised of

multiple media. Figures of stitched fabric recall her earlier "personnages."

But the newer pieces are soft, doll-like compared to the totemic wood

and bronze pieces from the 40s. New and old share Bourgeois' obsessive

processing of the past and, as in all of her work, this exorcism functions

as springboard to many other issues lodged in her consciousness: femininity,

self-image, sexuality, mortality. |

|

Born in 1911

in Paris, Bourgeois was involved at an early age in her parent's

business. At fifteen she began working in their successful tapestry

restoration studio. However, at that point she was already painfully

party to the marital drama epitomized by her father's philandering

and her mother's passivity. She fled what she describes as this

"nest of nuts" to study math at the Sorbonne which, at

twenty-five, she gave up for art. In 1938, newly married to the

American art historian Robert Goldwater, Bourgeois arrived in New

York. Rather than taking up the common modern cause, the anarchic

path of her work became a way to affirm herself and her past through

differentiation from the status quo.

|

|

|

|

Having

worked for so many decades in solitude, Bourgeois' international recognition

over the last two decades, beginning with her first museum show at

MoMa in 1982, has done little to change her course. Her commitment

to the personal throughout the formal reduction of Modernism and Minimalism

made her a galvanizing force for the post modern subjectivist movement.

Yet hers was not a reaction to contemporary movements, but a force

that began with the Surrealists with whom she consorted in Montparnasse

in the 30s. |

|

The vindication

of belated acclaim is surely sweet, but for Bourgeois it is incidental:

"I don't need

success. It's not what motivates me. Though success is sexy."

And success in the art world is not so easily opted out of if one

wants to continue producing work for public consumption. It is also

demanding, especially for someone so entrenched in her own life.

The recognition bears public responsibility—if only to refute

inaccuracies of interpretation—and Bourgeois vacillates between

candor and the caginess of obligation. It seems that the confessional

approach she takes to certain parts of her past is a tithe she pays

for the protection of other domains. Though a mother herself, she

speaks very little of her own family, as if to shield them from

prying eyes. Or perhaps, her work is purely autobiographical and

it does encompass her children to the extent that they are a part

of her. In some ways they are her most successful sculptures of

all.

|

|

|

|

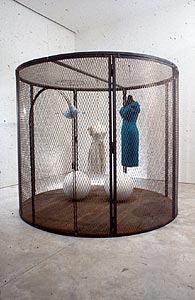

Bourgeois'

new works are haunting. They range from the aggressive emotion fully

figurated in Rejection, Hysterical, and We Love You

to the more familiar psychosexual symbolism of abstracted works like

Cell XIII and Untitled. These vivid three-dimensional

tableaux created from fabric sculpture share the complex and explicit

narrative of traditional tapestry. Other untitled pieces resemble

stacks of children's building blocks constructed from fragments of

actual tapestry. But the artist is resistant to neat assumptions about

her work coming full circle with her past. "The

idea of restoration is deep within me." However, she

is quick to refuse textiles any privilege, despite her beginnings

in tapestry: "I am not interested in

any one material. The materials are just materials, and they are there

to serve me." And some serve certain ideas better

than others. Cheim & Read describe a shift in message via materials:

"The images of severing and fragmentation in the earlier periods

of Bourgeois' work associated with the father is replaced in these

works by the activity of binding and holding together, associated

with the mother. Stitching becomes a form of healing. Fragments become

ordered and unified, edges become softer. The integration of the parts

represents a desire for restoration, reparation and reconciliation." |

|

|

|

Despite her

age, the physical aspect of creating art remains at the core of

Bourgeois' ability to reconcile past with present: "The role

of my own body is crucial. There is anxiety at the beginning of

the process, and hopefully in the end the tension in the body is

released." Creation conflates emotion and action, offering

new energy and perspective: "Art should help you to be able

to deal with other people. It should give you insights into yourself."

But it is an ongoing struggle, one in which the artist's stamina

and tenacity is recorded by decades of powerful visual testament.

"I want to be at peace with myself

and others. And that's hard." Assuring-happily for

the viewing public-that her process, like Penelope's, will continue

indefinitely.

|