| by

Mark Katzman

In writing about the work of John Gurche I must admit a bias right off the bat. I've known him since we walked together as school kids along creek beds in Kansas. I was just along for the company but John was already hard at work gathering skeletons of any creatures he could find to take back to his basement laboratory for study. Even then his course was set. In the field of paleo-art, John Gurche's work, in both painting and reconstruction, rests at the pinnacle. His work resides in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, The Field Museum in Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. You have seen it on the covers of National Geographic, Natural History, Smithsonian and Discover as well as in books such as The Rise of Life, by John Reader (Knopf, 1986). You may even have held it in your hand and sent it to a loved one or bill collector as he was the artist of the U.S. Postal Service dinosaurs issued in 1989. Gurche, 50, lives in Denver with his wife and three children. I spoke with him on February 25th, 2001 at the house of a mutual friend in Kansas City where a reunion was taking place of the rock band we played in back in the early 70's. One little known fact about Gurche: he's also a hell of a drummer.

|

|

|

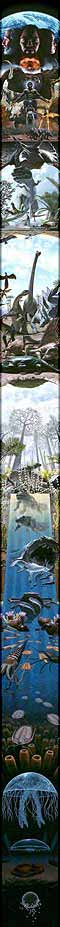

| What kind of planning was involved for the Column of Time project for the Smithsonian? |

They only had a nebulous idea of what they wanted, which was great. I really wanted a painting that represented the evolution of life from about 700 million to present, using groups that were important at different times in earth's history. So the fact that it was wide open and they didn't know what they wanted was a great thing to me because I could really start kind of dreaming it up and putting down on paper the various sections of the thing and how they relate to each other and just really be free with that. I knew enough paleontology to begin to get the initial designs right away. I was obsessed with the Tower of Time. I'd be riding the subway drawing little sections of it on the back of an envelope. It was a very happy time. | |

How long did it take to complete? |

The whole thing took a year and a half. It was two paintings, two time columns. You do a "little" one whenever you work for the Smithsonian. The 7ft. one is a tight color version, virtually identical to the big one. I painted it before painting the 30 ft. one. | |

How much guesswork is involved? |

There's always some guesswork when you're reconstructing the past. You never get the complete picture from the fossil record. | |

Is there artistic leeway? |

There's a little bit of leeway, yeah. But the more you know about it the less leeway there is. | |

How do you tackle a reconstruction?

|

When I'm asked to do a reconstruction the first thing I have to do is work with the skull. The first part of it involves reconstructing the skull, and if there's any distortion, correcting that. Maybe casting and molding it and bending it so the distortion is corrected. That sort of thing. I consult with anthropologists during that phase of it. And then it goes into this thing where I've done this really intensive body of work dissecting Great apes and humans and what I'm looking for is relationships between the bony tissue and the soft tissue of the face and head. I'm looking for rules that are so robust that they apply not only to humans but also to African apes. African ape faces and human faces are very different. You might think there would be very much in common there but it's not really true. There are a number of rules that apply to both, as far as the relationship between bony anatomy and soft tissue. Then it's not too big of a leap if you find something that holds for gorillas and Pygmy chimps and humans. It's not too big a leap to use those for human ancestors as well. So my methodology developed out of all that dissection work and finding some predictive value in the bones themselves. You look at modern skeletons and it tells you how to read a skeleton in terms of what soft tissue is connected to it. | |

How long does it take to build a reconstruction? |

The whole thing takes about 5 months. About 3 and a half of that are the slow building of tissue up from the skull, muscle by muscle, gland by gland. The last bit is casting it in a flesh-like substance, implanting hairs and all those realistic touches that bring it to life. | |

It's a very detailed process. |

If it doesn't read as something that's real and alive to people then there's not really much purpose in doing it. I think the reason we do it is because there's a need to connect with our past, and there's no better way of doing that then to be able to look into a face and see that individual as alive. | |

Does it ever get eerie? |

Sometimes there's an eerie feeling that the thing I'm building is no longer completely 100 percent made of plastic, plaster and clay. There's some semblance of the original individual looking at me while I'm building it. | |

Did you work with the Iceman?

|

I did get to study the body but only after the fact because the Austrians who had it at the time we're keeping it very close to the vest. They weren't letting in anybody to study it or even photograph it. The National Geographic photographer apparently got about 30 seconds. He was ushered into a room, took a few shots, then ushered out. They published about the skull in particular, measurements and also CAT scan images from a great number of angles. I had all that material and used it to generate a skull that was identical to the one that they had imaged inside the body. I didn't actually see the body until after the whole thing was finished. I went over there to see if everything I had done, and everything that I thought I was seeing–little hints in the soft tissue from photographs–I wanted to see if I got that part right. I planned a trip over there but at the last minute National Geographic pulled the funding because they didn't think that I was going to get in so I just went ahead anyway and I did get in. The build-up to seeing the Ice Man's body was really tremendous. I was told by virtually everybody that there was no way I'd get in, including the right-hand guy of the main man who makes the decision. I went out with him for a drink the night before and he said, "No. There's no way." But I gave them a slide show of the work I'd done for National Geographic and the reconstruction and gave them a point-by-point anatomical description of what that was all about. And they could see I was serious about it. Then the guy who was controlling things decided to let me in. So there I was in a waiting room full of German-speaking scientists. They were having a conversation which I didn't understand, except for the words scrotum and penis …blah blah blah blah scrotum, blah blah blah blah penis. As it turned out, although they'd published that the penis and scrotum were missing, suddenly they had found them. The translation I read later was that the genitals were there all of the time but they were just very…very… flat. [laughs] So there we all were when suddenly we got the ok and we all went downstairs and got suited up in surgical garb. The build-up was just so tremendous that I started feeling really light-headed and physically weird. And I thought, Oh, this is great, I'm gonna walk in, faint and fall into the Iceman's arms. But luckily that didn't happen. | |

What was your involvement in Jurassic Park? |

Amblin productions called me in the summer of 1990 to work on the pre-production for Jurassic Park. When they said it was Amblin calling they were kind of expecting a gasp or some surprised reaction from me but I didn't know who Amblin was. Oh, it's Steven Spielberg's movie company, they said. They wanted me to first work on the Tyrannosaurus, so I did anatomy and accurate reconstructions of the critter. Then they asked me to work on the Velociraptor segment. And they wanted to talk about everything from plot segments that might be done with bringing a dinosaur into the twentieth century, to the visual aspects…almost the character of the dinosaur. I've always viewed Velociraptor as probably the scariest and creepiest dinosaur. So a lot of them were night scenes about Velociraptors trying to get into the Visitor Center or being in the library with one of them right on the next row, you can hear it moving around but you can't really see where it is. I did a lot of drawings like that and had a great time. I came up with some plot segments which were in the script for a while but later got canned. And I was unwittingly responsible for maybe the least scientific detail of the anatomy, which was the neck frills on the Daspletosaurus, the spitters. The art director called me one day and wanted to talk about plot segments. He said, I want something where the paleontologist, by his special knowledge, gets them out of a jam. So I said, OK, let' see, maybe when they're taking the tour initially, before everything goes wrong, they see two male dinosaurs of some species facing off, having an aggressive encounter, and one of them has an inflatable portion of its anatomy, like birds and frogs, and it blows this thing up and it scares off the other male, and then later in the movie you see the humans get trapped by that same kind of dinosaur, it's backed them into a corner or something, and then suddenly the paleontologist looks over and sees this umbrella that's the same color–let's say black and red stripes–makes the connection, picks up the umbrella, unfolds it and makes it run off. That got incorporated as part of the plot but then they took it out and only left the anatomy in. | |

| Next Page > | ||