|

<

previous page

|

|

How long, generally, does a

painting take you? |

Usually

about 4 months if it's a painting that's somewhere in the neighborhood of

both sides of a National Geographic opened up. |

Did you study art formally? |

No. The only art

class I've had was in 8th grade. My parents still have the drawings

from that and they're just awful. Every once and a while when I visit they

get them out and we just laugh. But I was drawing things that I wasn't inspired

about, like grapes [laughs]. I loved doing drawing and painting as a kid,

like most kids do, I just never stopped. I kept painting on the side while

I was studying anthropology and paleontology in grad school and was able

to combine them. |

Do you have a vision of the

painting from the beginning? Do unexpected things happen while you're

working? |

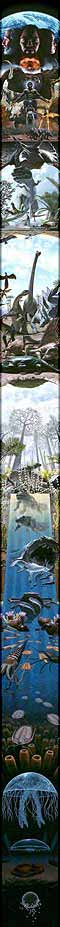

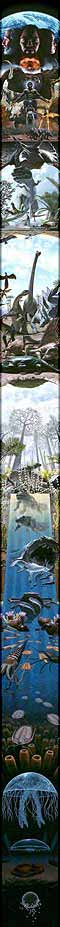

The usual paintings

that most people have seen are pretty well planned from the beginning. I

try to base them on a moment of inspiration, working with a design that

I really like before I start the painting. But sometimes little serendipitous

things happen along the way. There's a painting that was in National

Geographic--I hadn't painted the head of the critter yet, it was

still a black silhouette, and I got it up to a certain point and it was

beautiful, it looked like an Alfred Hitchcock dinosaur because this one

animal's head was totally in shadow and blacked out. |

|

I'm curious about your painting,

"A Barasaurus Protecting Her Young," depicting the spectacular

Barasarus mount that's on display in the rotunda at the American Museum

of Natural History. Was that pose decided by the museum?

Yes. I was asked to reconstruct

it.

|

How do you decide the color

of a dinosaur? What liberties do you take? |

That's kind of

wide open. When I worked on the reconstruction painting of "Sue"

that's now hanging next to the skeleton at the Field Museum, the coloration

of the animal had already gone through a formal review process, which seemed

kind of funny because, obviously, we don't know what color they were. I

guess they didn't want it to be outlandish. All you can really say is that

modern relatives of dinosaurs have color vision and use it in their social

behavior, for display and so forth, so it's pretty reasonable to think that

dinosaurs did also. |

What's the influence of Charles

Knight on the history of the depiction of dinosaurs? |

He was the founding

father of the field. A lot of artists and paleontologists were effected

by his work. They saw his paintings when they were kids. I remember when

I was very young, staring at his painting of an Allosaurus standing over

a Saropod carcass. I stared and stared at it and thought it was a photograph.

I knew there was something wrong with having a photograph of dinosaurs and

tried to get my mom to explain it to me. But it did what I hope to do when

I paint a picture, which is to transport the viewer back in time and to

see it as not some Fairyland world, but as a real, living biological system. |

What is it like seeing the

cave art in France? |

It was a very powerful

experience, not easy to describe. Caves are magical worlds anyway. They're

kind of a place of the "Other", an alternative to the world to

what we generally see, of trees and sunshine. It's another world down there.

It makes sense to me that they were sometimes used as sanctuaries, holy

places, and maybe as places where shamans took their journeys to the Dream

Time or whatever "other" world they have. It's easy to think of

the caves as being able to offer a real place to do that. So going down

there and standing where they did and looking at these paintings, especially

when they're really good paintings, like Lascaux or Altimira is just a stunning

thing. It's so much wonder that you almost can't stand it. For about 4 years

I was a co-leader on a tour that went into those caves. We took all sorts

of rich folks there. Some of them seemed like really jaded people until

we got inside and they wept like babies. |

Were you given much liberty

with the dinosaur stamps? |

Not too much. They

didn't have set scenes, but they'd picked out the animals. It's pretty restrictive

to what you can do on a stamp. It's not exactly a venue for self-expression

on a painting that's about an inch and a half wide [laughs]. Usually the

artist does it 5 times up but I was already neck-deep into another project

so I said I'd do it but only if I can do it 1.5 times up. So it was only

a little larger. |

Tell me about your current

projects. |

I've always loved

the way certain Renaissance artists drew anatomy. It's sort of messy. It's

almost like they're illustrating a thought process. Very loose line drawings

of anatomy that Leonardo and Michaleangelo did. Though Michaelangelo burned

a lot of his. I've always loved the way they delt with anatomy. It's probably

the best style for capturing anatomical details. They have a powerful aesthetic

quality. So I wanted to start working in a similar way. It was hard at first

because I'm used to working so tightly. I had to get real loose before

I could begin. My first response is to draw a line and then say, Oh my god,

how am I going to make the second line parallel to the first line. But you

can't do it that way. You've got to be much looser or it won't work. The

first twenty times I tried it I couldn't do it. But then it started to work

out. This all came out of doing anatomical research for the paintings I've

done for National Geographic and other publications. Sometimes you

come upon anatomical forms that are aesthetically more powerful then the

paintings they're supposed to inform. So after a build-up of experiences

like that until I just had to start drawing. It's taking a time-out from

commissioned work to draw–fossil skulls that I've worked with or gorilla

anatomy or whatever it is. They're mostly larger than the other work. They

start out as drawings but kind of take a left turn and rely heavily on accidents.

They almost never turn into what I had planned them to be. It's a very fun

process to be able to go with those left turns when they happen instead

of making them conform to a strict plan. It's called Lost Anatomies. |

| You're

working at the nexus of science and art. |

To me there's less

of a dichotomy than for some people. Their aims and methodologies are different.

But there's an awful lot of crossover in terms of the motivation for doing

both. I think a lot of scientists are aesthetically motivated but I don't

know how many of them would admit it. The scientific stuff and the aesthetic

stuff feed each other. I think an aesthetic feeling for the subject motivates

a lot of scientists and artists alike. |

Doesn't the art transcend the

science in that it makes "something else" happen? |

I think it's the

subject that makes the "something else," I don't think it's the

art. To me it's that skull sitting on the table that's the center of it.

It's those things in their own right that can be so aesthetically powerful

that it just makes you have to draw it. And the big surprise to me is that

more paleontologists and anthropologists don't also want to be drawers and

painters. I don't know if I think of the artist as transcending something.

It's all coming from the thing itself. And the art is a way to capture it. |

|

©2001

Artzar - All Rights

Reserved

|